Just when we thought it was safe to think of the workplace as a stable, predictable environment in which to earn a living and build a life, job security is slipping into reverse. Precarious (irregular) employment is becoming more common, governments are working at increasing the minimum wage and employers are still ‘hiring’ young people but not paying them because, those employers claim, they’re volunteers. The law now takes a dim view of such practices.

Deloitte (‘Six trends to watch in alternative work’), RBC Royal Bank (‘Predicting Tomorrow’s Workforce: More ‘bots, More Skills, More Anxiety’) and McKinsey Global Institute (‘What the future of work will mean for jobs, skills, and wages’) tell us that technology and higher education will figure prominently in the future of work. But when the rubber meets the road, neither comes with a guarantee of employment, lifelong or ottherwise. The 40-hour workweeks and permanent jobs with benefits and pensions we’ve always wanted for our children are at risk of becoming an endangered species.

(To read about a real-world application of what you just read, please visit ‘GM Gets Ready for a Post-Car Future‘, FORTUNE 500, June 1, 2018, for a description of how and why GM CEO Mary Barra is changing the environment and culture at the 110-year-old automaker.)

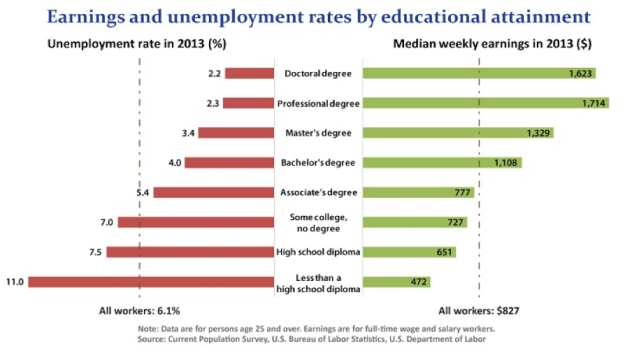

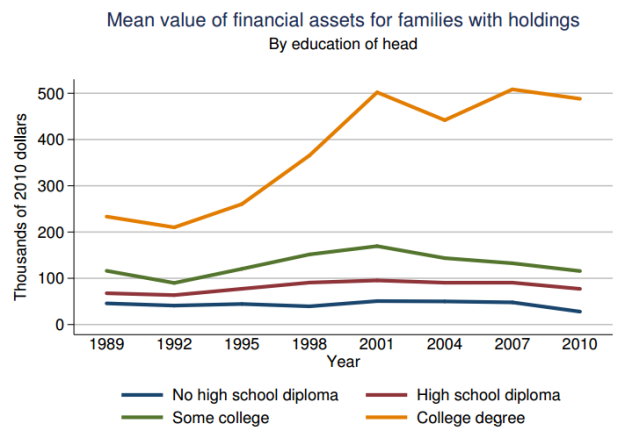

Parchment isn’t delivering financial security and above average lifetime earnings the way it used to when the world was a more flexible and accommodating place. Demand for university graduates has never been stronger and more students are enrolling because of it. There are now so many degrees on the street that our children have to navigate buyers’ markets for talent, just-in-time work-forces and environments that reward employers for dragging out the hiring process. By 2025, enrollment at the world’s 26,368 universities will stand at 260 million. More graduates, more competition for work.

There are more different kinds of work to apply for and more new places in which to find it than at any other time in history. But résumé screening statistics show that only 10 job applicants in 100 understand what the labour market is and what makes it tick well enough to motivate prospective employers to call them in for an interview. They also show that only one of those 10 applicants will be offered a job. What they don’t tell us is how the work is going to be structured, how much it will pay, how long it will last and how employees and employers are going to relate to one another.

Our education system isn’t producing graduates who can make the connection between what they learn in school, labour markets, how employers determine what a degree is worth, and going for the brass ring. Every one of the 7.3 billion people on the planet wants their shot at that brass ring.

The National Geographic TV series One Strange Rock aired an episode entitled Survival on April 10th. It showed what survival is in a way that only National Geographic can. BBC Earth is doing the same. Human beings created the technology and shaped the attitudes that define the environments in which we live and and work. Our kids are going to support themselves in those environments.

Grizzlies pluck migrating salmon out of the air as they swim upstream to spawn. The streams are the labour market, the salmon are employment opportunities. Grizzlies know what salmon are, in what streams they’ll be running and how to catch them. We have to teach our children how to find the streams where the salmon run. Whether they’ll choose to fish when they get there and how well they’ll fish will be up to them.

The world as Deloitte, RBC and McKinsey see it has implications for our children. They’ll have to learn about those implications at our knee because they won’t be learning about them anywhere else.

I teach parents and their young people how to connect school, labour markets, how employers determine what a degree is worth, and going for the brass ring. It’s a skill they’re going to need for the rest of their lives. Grizzlies already know that.

Neil Morris

President

Personal Due Diligence